Indonesian Government launches mis-information campaign using fake social media accounts

November 12, 2020

Originally published by Bellingcat

A new online influence operation that seeks to counter West Papua’s independence movement appears to have emerged on prominent social media sites. The discovery comes roughly one year after a similar network of fake accounts was uncovered by Bellingcat.

Although the new web of between 100 and 200 accounts has made little impact thus far, it appears to stretch across Twitter, Facebook, Youtube and Instagram, utilising methods that have not previously been documented in the online conversation around West Papuan independence.

These include the deployment of accounts with fake profile images generated via machine learning tools as well as the use of Dutch and German language posts that appear designed to influence the debate abroad.

Yet the network also employed practices uncovered during previous investigations, such as the use of fake accounts with stolen profile images, anti-independence infographics and a self-hosted news site to spread content supportive of special autonomy for West Papua as opposed to full independence.

Separate research by the Leiden University in the Netherlands appears to have been the first to publish findings on the new network after it released its own study earlier this week. It is unclear whether the accounts uncovered in this research are the same ones found by Bellingcat which has also been looking into the issue independently for the past month.

Bellingcat’s previous work on this topic revealed a large cross-platform influence operation relating to West Papua in October 2019, attributing it to a Jakarta-based communications company called InsightID. Social media platforms subsequently purged much of the content, pages and accounts involved, while InsightID closed and disappeared completely.

Who or what is behind the new network of accounts is not clear at this stage.

Bellingcat has made Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and YouTube aware of the accounts uncovered. Twitter stated it had “suspended” the accounts highlighted in line with its platform manipulation and spam policy. YouTube and Facebook, which owns Instagram, did not respond to requests for comment before publication.

Conflict on the Streets; Domination Online

The debate over West Papuan independence has been long-running and bitterly fought.

A mineral rich former Dutch colony, West Papua became part of Indonesia following a controversial 1969 referendum. Many West Papuans still pine for independence and claim they regularly face racism and discrimination from Indonesian authorities.

However, Indonesia continues to stand firmly against the prospect of West Papuan independence.

Recent demonstrations saw Indonesian troops clash and reportedly open fire on pro-independence protesters.

But the argument and battle is also being waged online, with efforts seemingly being made to manipulate the conversation.

As our research found, the use of computer generated images to burnish fake user profiles appears to be a key method in this operation.

Yet this practice, while intriguing and tricky to immediately spot, eventually helped unravel this latest inauthentic network.

Fake Profiles

These days, creating a fake profile image of a non-existant person is easy and can be done at the click of a button via websites such as thispersondoesnotexist.

While such tools work well, they are not without flaws.

Images may look perfect to the naked eye, but upon closer inspection can reveal blemishes such as an unmatched set of wrinkles or imperfect symmetry.

The images are created via what’s known as a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN). This is a class of machine learning frameworks that creates new images from a selection of old real world images.

Influence operations are likely to use GAN because doing so prevents researchers from using reverse image search tools to identify pictures that may have been stolen from social profiles, as has happened in previous inauthentic influence operations.

Despite this, researchers are beginning to identify ways of analysing GAN images. One key giveaway is the position of the eyes. They always remain in the same place, allowing researchers to develop techniques to spot them.

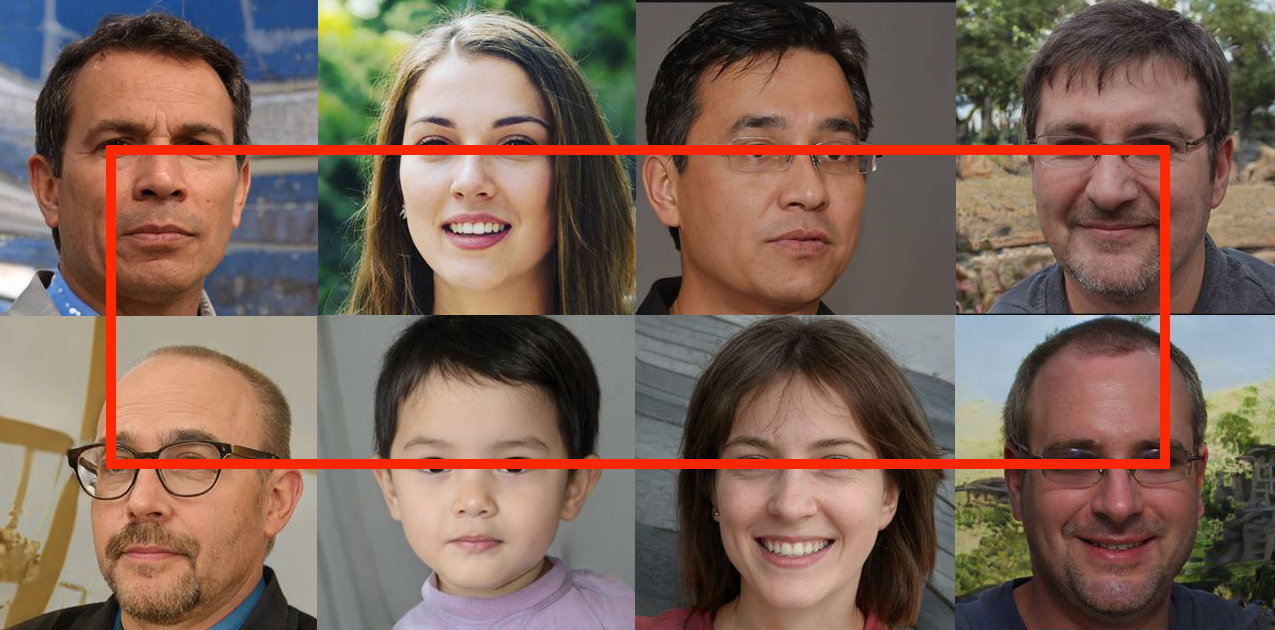

Ben Nimmo of social media analysis firm, Graphika, ‘layered’ a selection of GAN images, identified in a recent inauthentic network. As can be seen in the image below, the eyes are in the exact same place, something that would not happen with genuine photographs.

Network identified on Twitter

The latest network related to the issue of West Papuan independence was first identified on Twitter through monitoring the tags #WestPapua and #PapuanLivesMatter.

The second hashtag was widely used after protests in West Papua that took inspiration from the Black Lives Matter Movement in the US earlier this year.

It did not take long to notice that a number of accounts with very few followers were spamming these tags with content linking to the same few websites.

Closer inspection showed that many of the spamming Twitter accounts were created in either June, July and August 2020. A telltale sign of an influence operation can often be multiple accounts with few followers, created around the same time and with a singular focus on one issue.

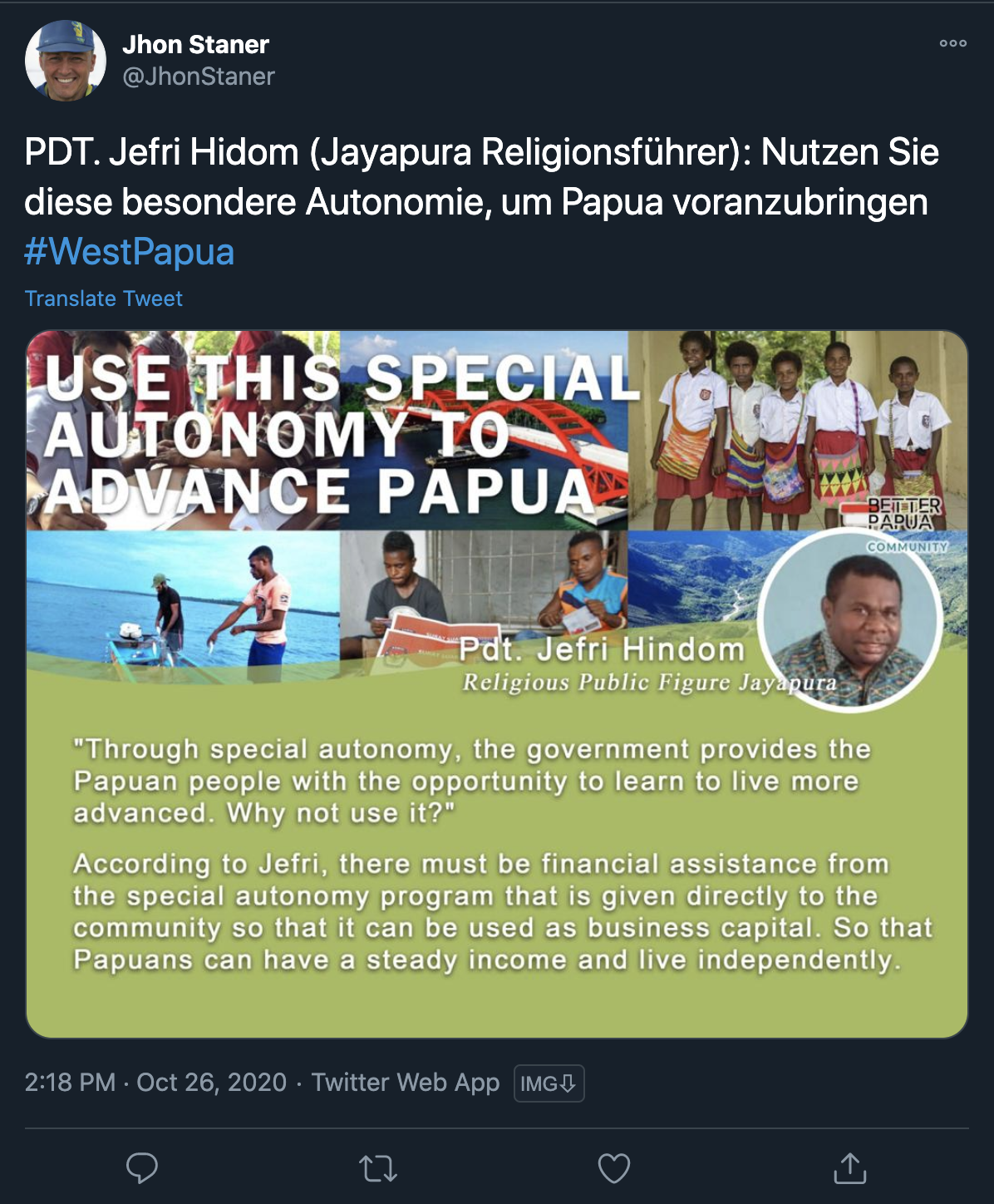

The screenshot below was one of the accounts created during this period.

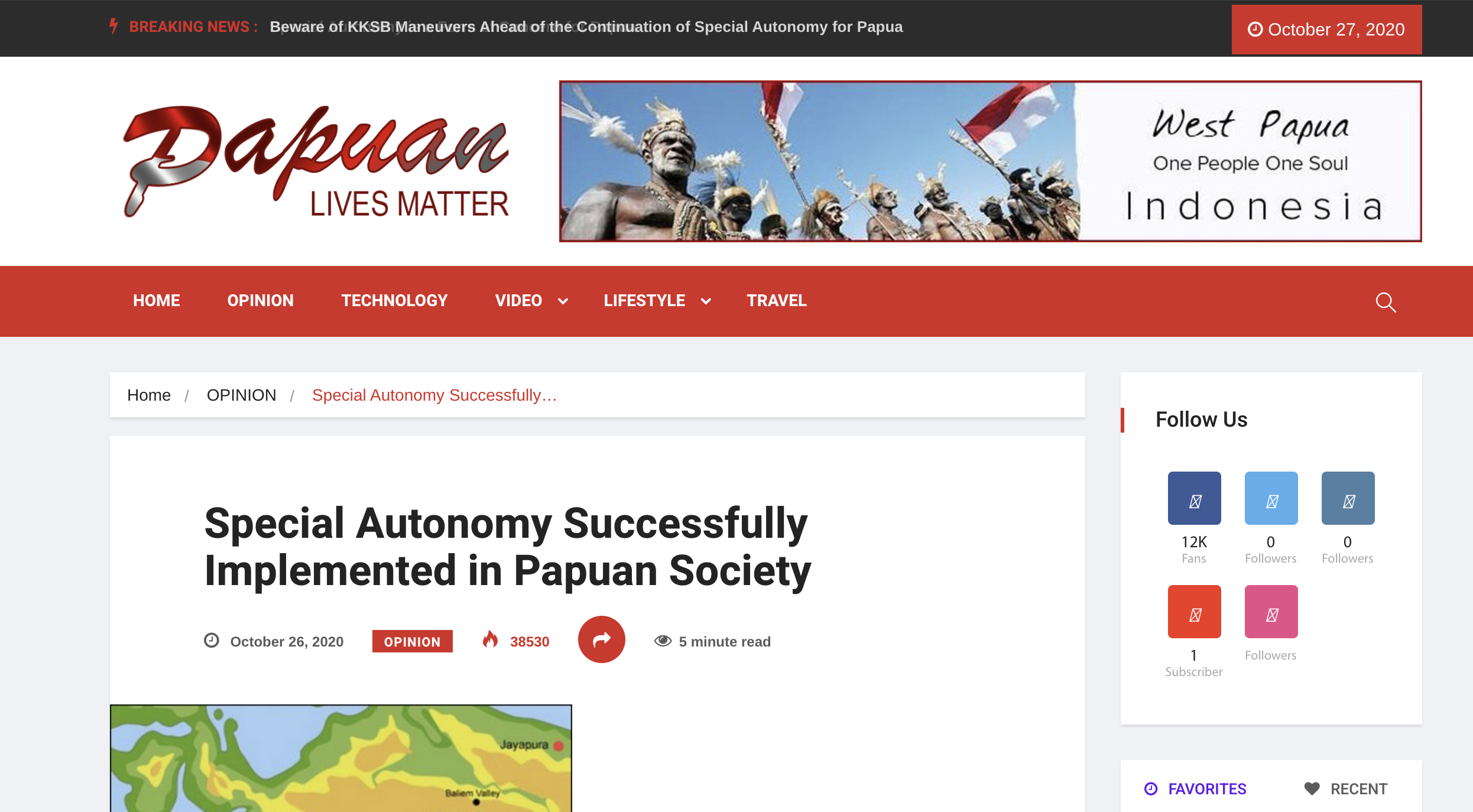

One of the websites the accounts in question appeared to be frequently linking out to was papuanlivesmatter.com.

The articles being shared generally offered support to the idea of special autonomy for West Papua rather than independence, were supportive of Indonesia’s good influence over West Papua and critical of any activists speaking out against special autonomy.

This investigation collected accounts that used the popular hashtags and linked to papuanlivesmatter.com over the past two months. Of those accounts, 21 were flagged for testing to see if they were using GAN generated images. This was just a sample of suspicious accounts posting articles from papuanlivesmatter.com, with many more showing profile images that didn’t use a human face or images that appeared to have been stolen from Instagram.

Below is a sample of those 21 accounts for the purpose of showing their details

Here are those faces in a tiled view.

By looking at the position of the eyes, which remain the same in each image, we can see that these appear to have been created by a machine learning platform.

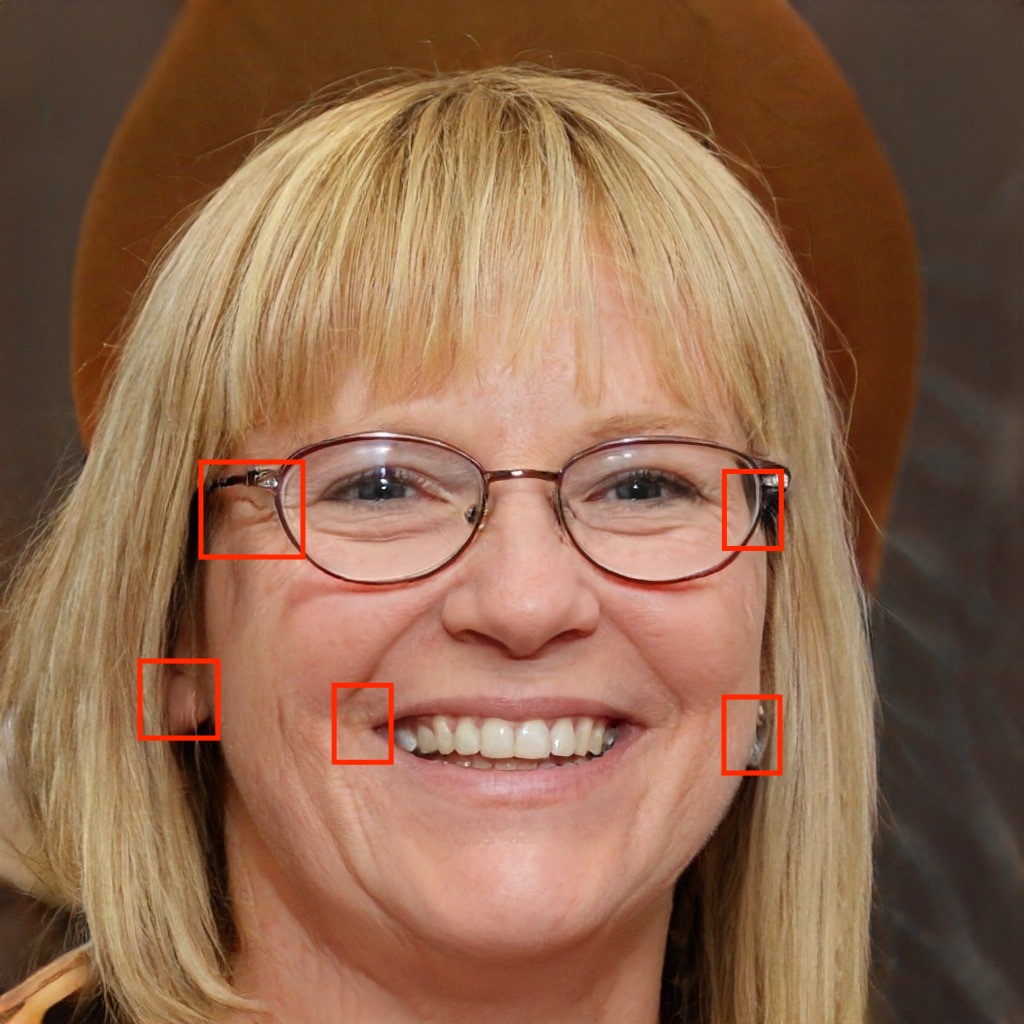

Digging down further into these images, there are also other tell-tale signs of synthetic generated faces.

The arrows in the image above highlight differences and blemishes, including eyebrows that don’t appear to match and a hat that has inconsistencies around the logo and visor, which appears to have a significant amount of extra material on the left hand side.

This image was used as a profile for an apparent German speaking account which posted about special autonomy and countermeasures against groups seeking independence, as seen below.

In some of the English-language accounts in the network, effort has been taken to include a short bio, such as the below account claiming to be an “australian reporter” [sic].

Other accounts communicate in Dutch, and some have managed to gain a respectable number of followers. Some of these followers appear to be authentic human Twitter users.

The network has a propensity to make claims of either fake news around anything that may cast the pro-independence movement in a positive light or to place doubt on many arguments used by pro-West Papuan activists and those in pursuit of independence.

An example of this can be seen in the tweet below which describes and links to the papuanlivesmatter.com site and an article about pro-independence parties allegedly creating ‘hoax’ news, or false news.

Network Identified on Facebook

Network Identified on Facebook

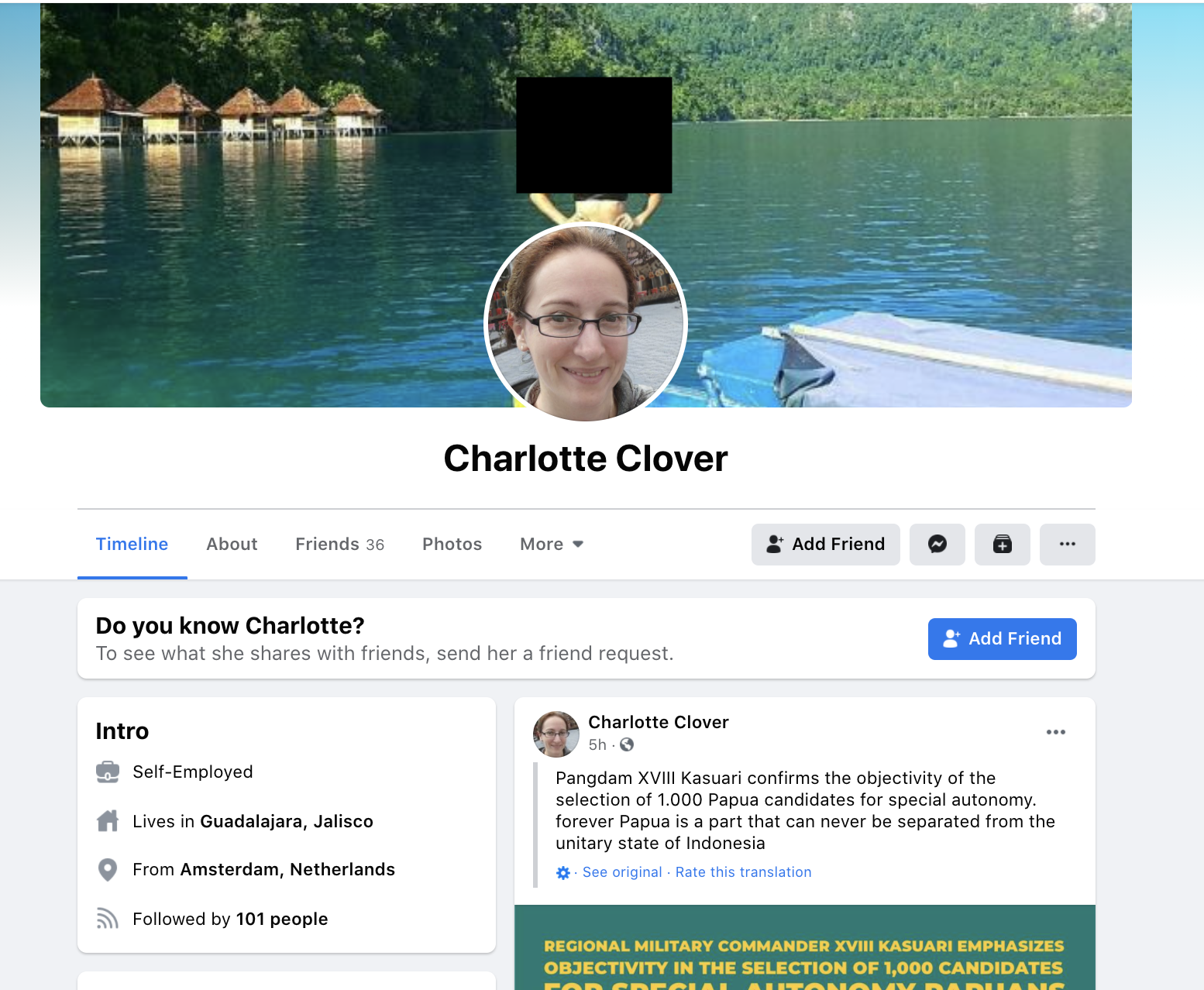

The influence operation also appeared to extend onto Facebook, utilising similar tactics as could be found on Twitter.

One of the specific terms we were able to use to find accounts posting the same content was “special autonomy in Papua.” Going through the ‘friends’ listed on these accounts, it was possible to identify further potentially inauthentic accounts. Repeating the search for Twitter content that was cross-posted to Facebook also revealed more accounts.

Below are some of the results of that search.

This investigation did not extensively search for all of the accounts that might be present on Facebook as part of this operation, but it did identify a sample of at least eight that would provide a method for identifying whether or not they were part of the same network that was present on Twitter.

The validity of those eight accounts was assessed based on friends, activity and profile pictures. Most had no friends, while three had at most 10 friends on Facebook – some of which linked to each other or more accounts that displayed similar characteristics as the rest of the network.

The profile pictures of the eight accounts, again, appeared to have been artificially created using a GAN method, as can be seen below.

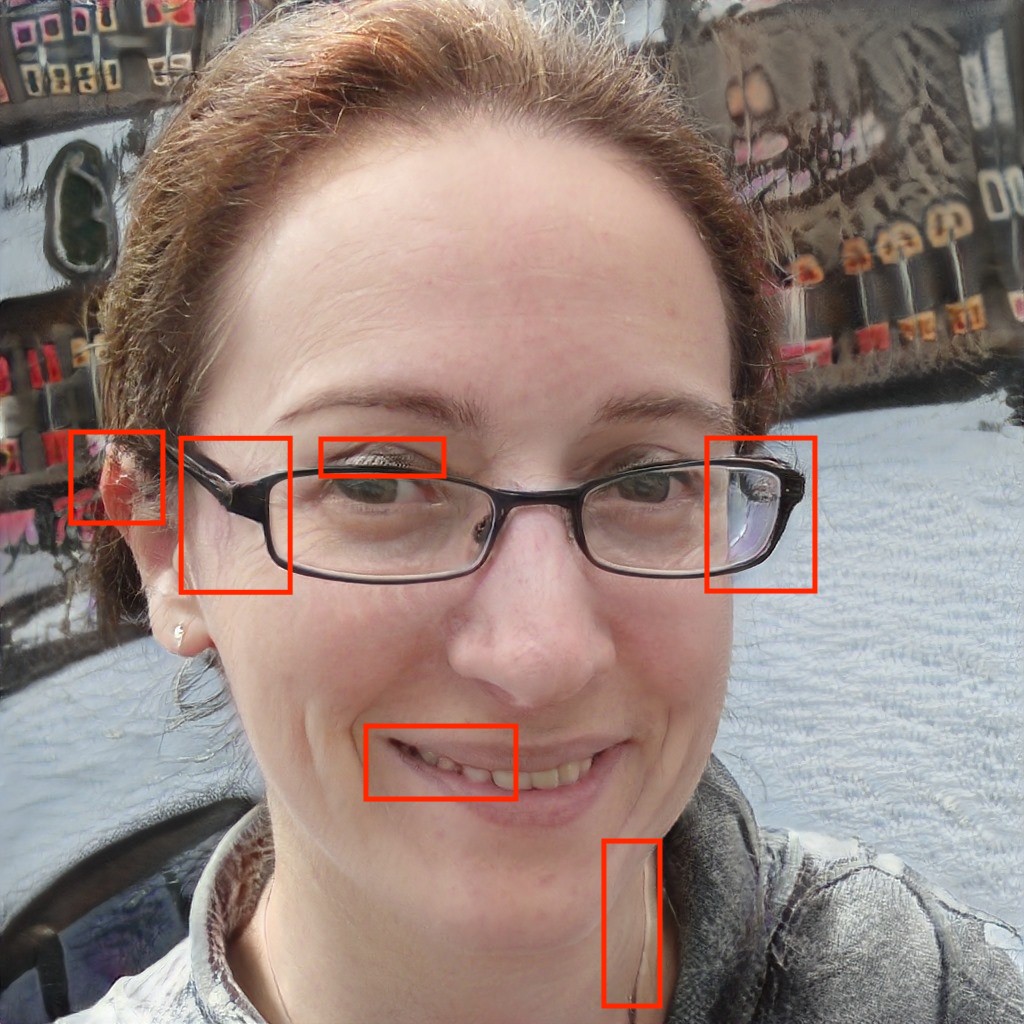

As detailed previously, suspected GAN images should always be assessed for extra detail beyond the position of the eyes.

For example, in the image below, taken from one of the Facebook profiles, we can see multiple points where the image failed to ‘blend’ correctly. Images including glasses can generally be a point of weakness for GAN created images.

In the boxes identified, we can see that there are extra lines, a lack of symmetry and unnatural curves that would not appear in a natural image.

In the next image, below, we can see that one of the ears has an earring, while the other doesn’t. The ear on the left is also slightly turned out. Several other inconsistencies are also present.

As for the content these Facebook accounts were posting, there appeared to be no normal human posting activity, details of hobbies or interests. The accounts appeared to exist solely for the purpose of posting content critical of West Papuan independence.

There were signs, however, that some of the Facebook accounts identified may have had a previous owner. Some had a substantial amount of human-user followers, and a number had original cover photos (these have been boxed out for the purpose of privacy). This could suggest that these accounts had been hacked or hijacked.

And the following.

Infographics appeared to be the standard means of amplifying the network’s message across Facebook. All accounts we found seemed to make posts with graphics detailing anti-independence sentiment at one stage or another. At times, they also link through to common urls. See below for an example of the image posting history of one account.

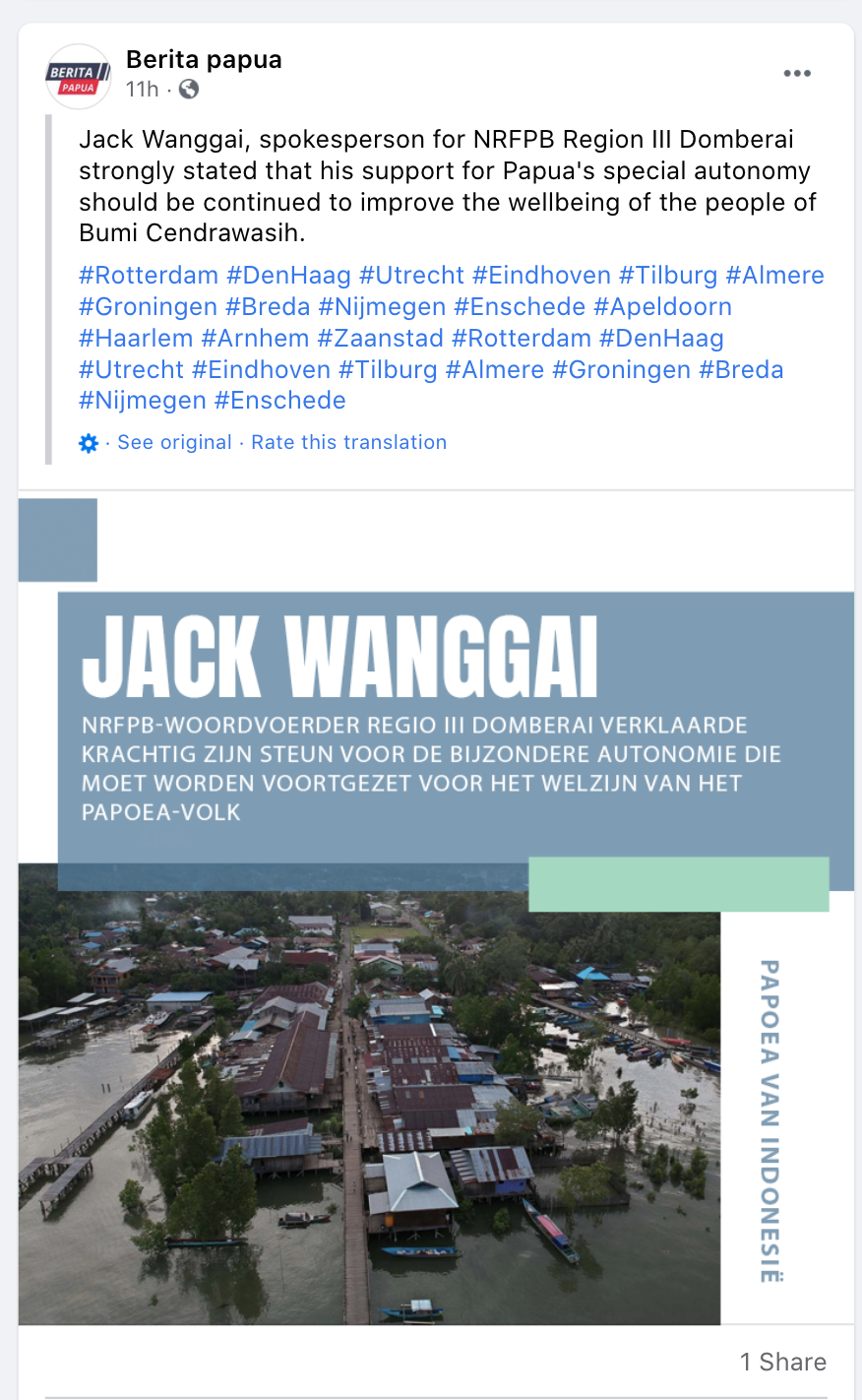

One of the new traits noticed in this network was the use of Dutch and German language posts to amplify the content, as well as English. The network we discovered in 2019 had primarily used English as a means of communication.

The new Facebook network also sought to tag towns in the Netherlands, likely in the hope of piggybacking off interest in content related to these locations. For example, a number of Dutch towns are tagged in the post on special autonomy below.

There are repeated uses of this tactic throughout the Facebook network. Below is another example using the same tags of cities and towns in The Netherlands.

The post above was made by a number of Facebook pages claiming to be a news source. These accounts also generally posted the same infographics that many other accounts in the network were posting as well as about the topics of West Papuan independence and the issue of special autonomy.

A screenshot of the most recent posts showing those infographics can be seen below.

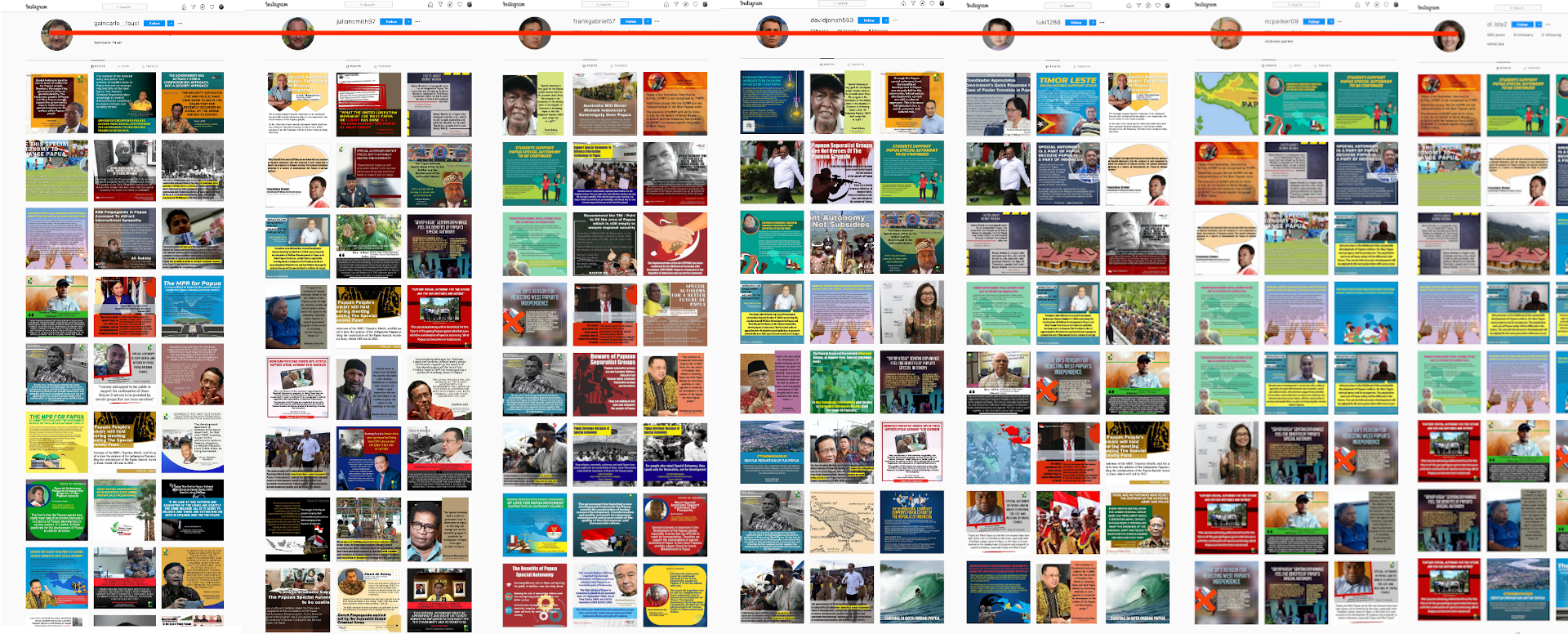

Network Identified on Instagram

Again the same style of accounts as seen on Twitter and Facebook were present on Instagram. These accounts were cross-posting the same infographics seen in the network previously, as well as using GAN created profile images.

The image below shows the posting activity of seven accounts with GAN profile images on Instagram. It appears infographics with anti-independence sentiment was all that the accounts posted.

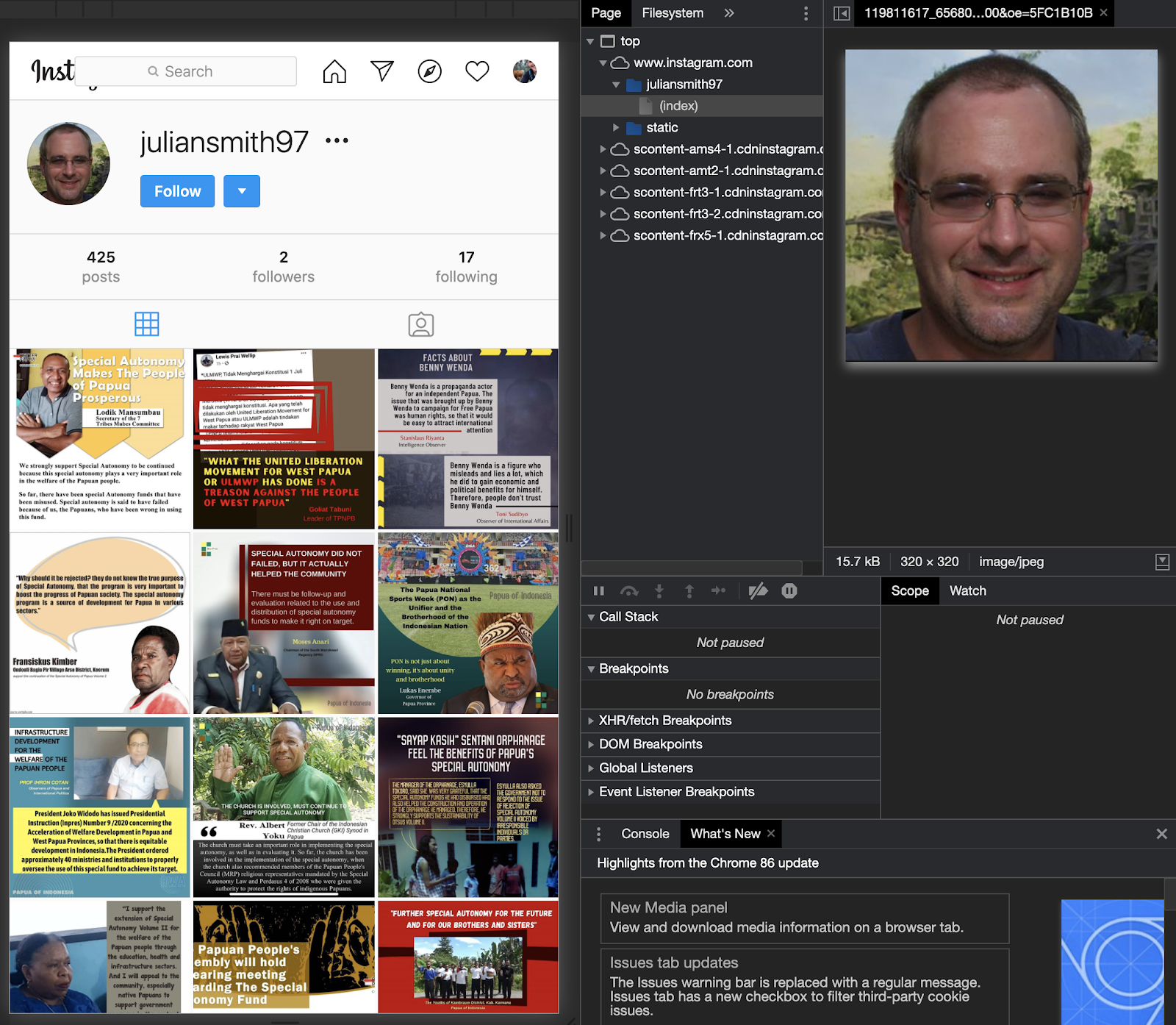

Through developer tools in Google Chrome it is possible to access a full size Instagram profile picture for closer inspection.

Below is a tiled gallery of a selection of profile images compiled from Instagram. Again, the eyes appear to be a giveaway as to their authenticity.

Again, the same process applied to identify artificial images.

To be clear, our research also found other suspicious Instagram profiles posting the infographics detailing anti-independence sentiment that appeared to show celebrities, anime characters, or pictures taken from elsewhere in the profile picture slot. It is highly likely that these accounts are fake as well.

Evidence of Network Amplification Through YouTube

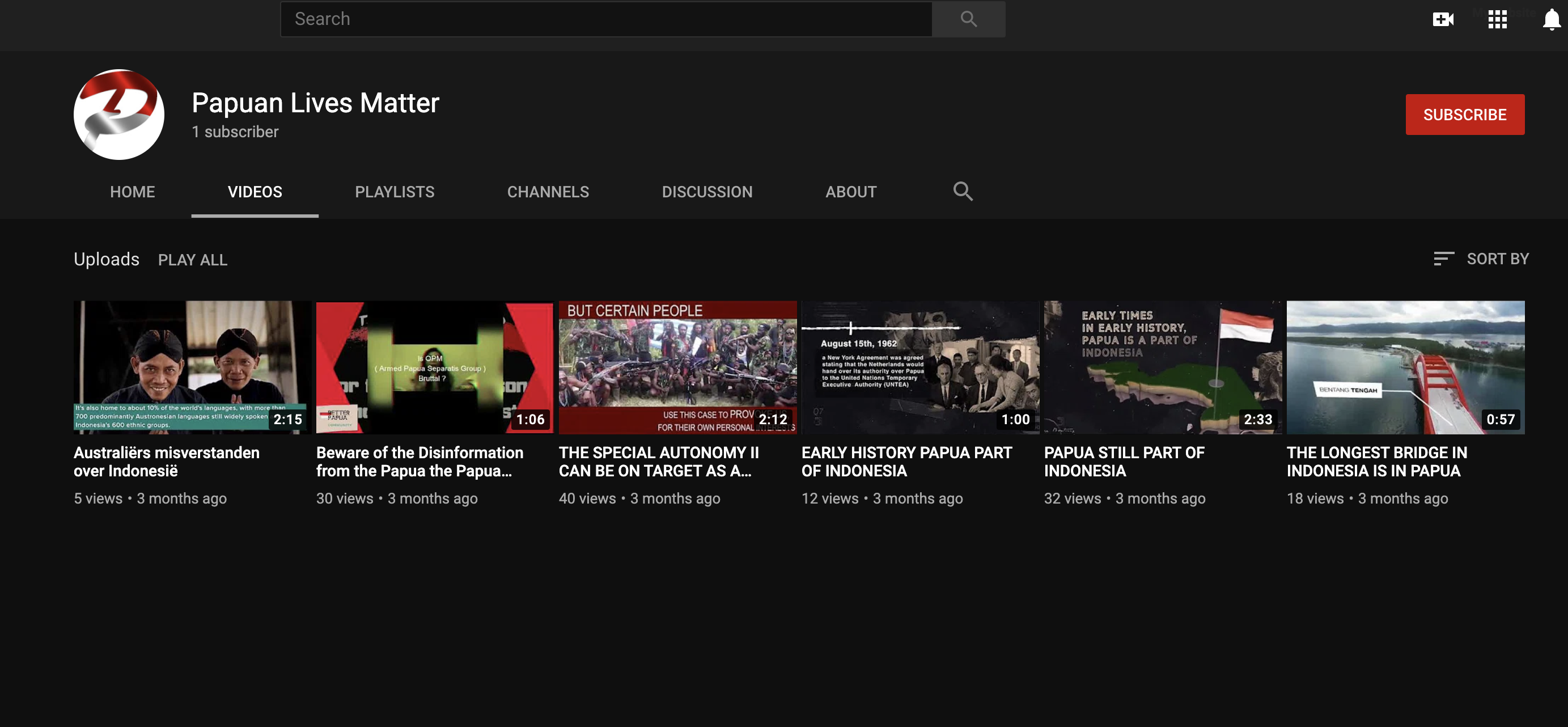

There is also evidence that suggests YouTube may be being used to amplify the content of the network.

The papuanlivesmatter website links to various social media handles of associated accounts. One of them was the site’s YouTube channel.

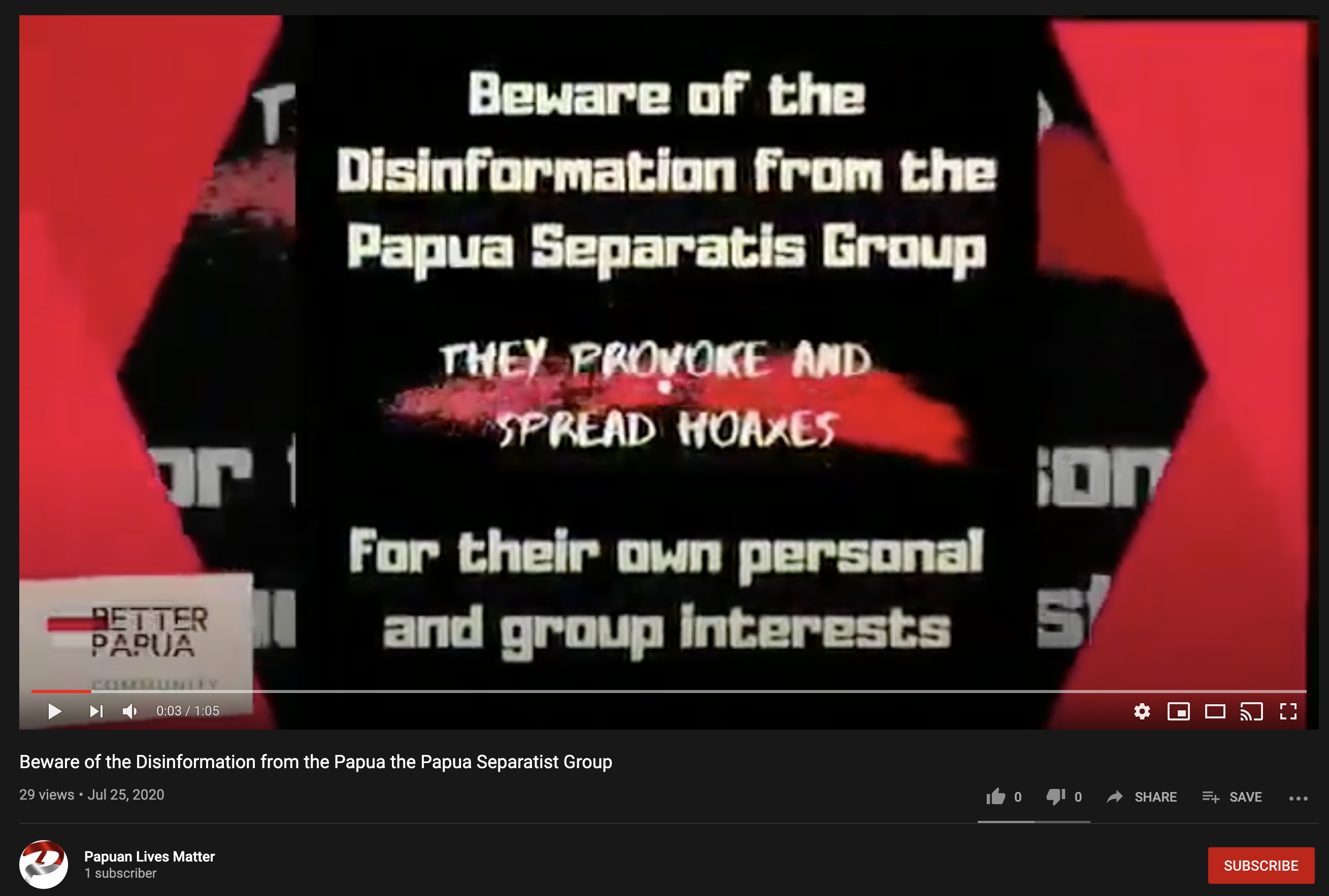

The channel contains content similar in nature to that found on the other social platforms, detailing why West Papua is better off as part of Indonesia and claims of disinformation from West Papuan separatists.

Ironically, the videos single out specific human rights activists such as Veronika Koman, claiming that they “provoke and spread hoaxes for their own personal and group interests”.

Another two YouTube accounts (below) were identified as uploading similar content. They used western names in their profiles and their uploads primarily contained short videos about West Papua under Indonesian rule, the benefit of special autonomy for West Papua and, again, attempts to discredit independence seekers.

Many of the video reports bear similar graphic design traits, style, subtitles and context to videos seen in past West Papua-focussed influence operations.

Below is a series of screengrabs detailing videos identified last year by Bellingcat.

We can see a similar style in the more recent videos, below, many of which have the branding “Better Papua Community,”

Some of these videos also feature on the papuanlivesmatter website which was regularly linked to by the inauthentic Twitter and Facebook accounts identified above.

Some of the recent YouTube videos have been given Dutch titles as well, a noticeable similarity to the posts made on Twitter and Facebook that have been detailed previously.

Like the Facebook, Twitter and Instagram accounts we documented, these videos appear to have had very little impact. Some have generated less than 10 views. However, they do indicate that considerable time has been spent to bolster the content this network has been designed to amplify.

Identification of Central Website

As seen in the above platforms, specifically Twitter and Facebook, the network links out to one site in particular, papuanlivesmatter.com

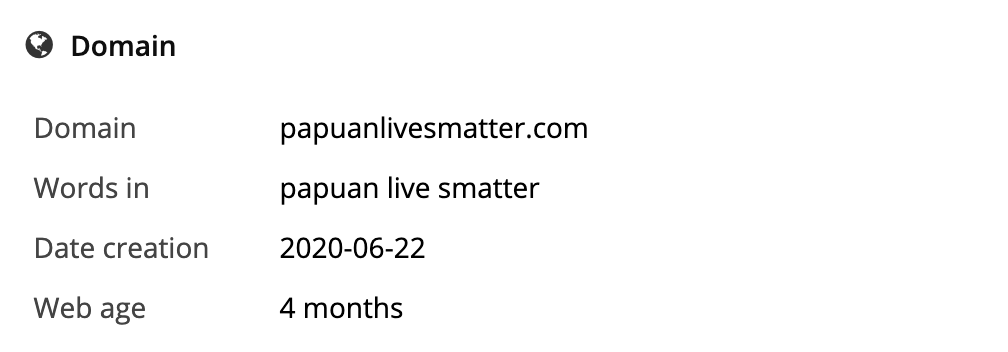

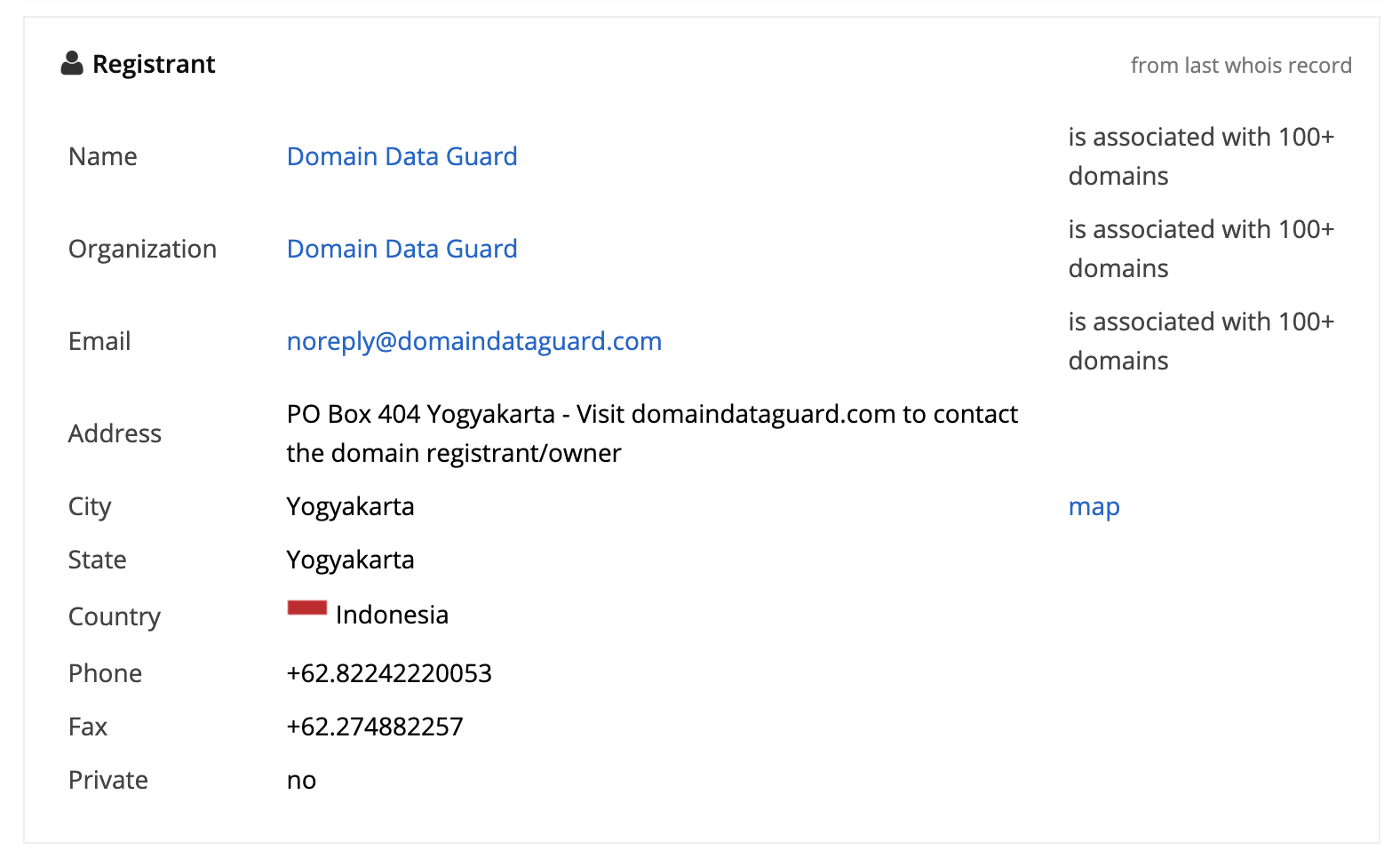

According to the registration details of the site, the domain was created on 22 June, 2020.

Despite privacy of domain registration details, the data registrant guard details are listed in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. While this is not conclusive, it may indicate the network’s origin and location.

There also appears to be no contact details for the website itself, with a “contact” tab linking to the website rather than an email address or form that would put a web user in touch with those running the site.

What seems clear from all of the above evidence is that a new information operation targeting West Papuan independence with a pro-Indonesian narrative has been operational on major social networks in recent months.

While the impact of the network has been small so far, the use of inauthentic user profile images separates it from previous operations as well as the use of Dutch and German languages and the tagging of Dutch towns in Facebook posts.

Whether social media firms are able to investigate further using the backend data to identify and attribute to the people or organisations responsible remains to be seen.